WaterMarks: An Atlas of Milwaukee’s Water

When City as Living Lab came into existence in the mid-2000s, founder Mary Miss hoped it would be a space for artists and scientists to collaborate in highlighting environmental issues like climate change, equity, and health through accessible direct experience. While each project has been vital in achieving this goal, Miss considers CALL’s latest project, WaterMarks, the initiative’s fullest realization to date. An “Atlas of Water” for the city of Milwaukee, it’s a multi-nodal interactive installation for understanding not only water, but also the many narrative’s of Wisconsin’s largest city — one that lies at the confluence of multiple rivers and Lake Michigan.

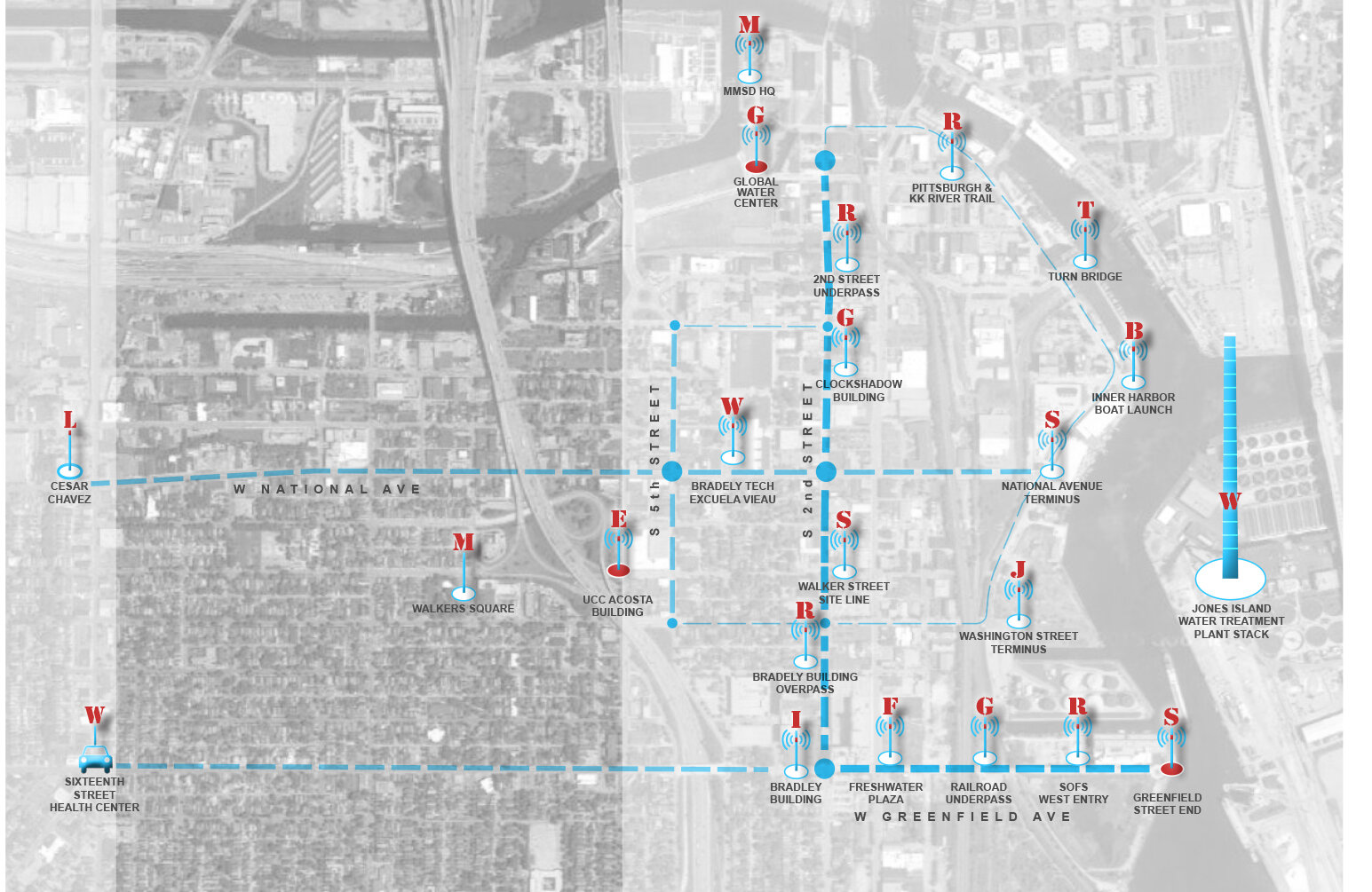

Upon completion over the next several years, numerous Milwaukee neighborhoods will feature WaterMarkers as loci of information on water conditions. Tangibly speaking, residents will encounter solar-powered, wi-fi equipped poles that function as interactive hubs for water conditions, infrastructure, and the city itself. Milwaukee’s first true smart city network, WaterMarks is already notable for the wide range of stakeholder involvement. Typically, smart cities are envisioned as a partnership between tech companies and local government. While certainly true of WaterMarks, the project also features input and work from community organizers, technology and energy companies, and other participants.

Like CALL’s work in restoring Tibbetts Brook in the Bronx, New York, WaterMarks is a massive undertaking. Beyond the interventions, the project will also include a series of public programs, citywide initiatives, and community events designed to further help create a tangible, intimate understanding of and engagement with water.

An Atlas of Water

The WaterMarks project has its origins in a 2014 symposium at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Miss, who had designed a section of the Milwaukee Riverwalk in the late 1990s, spoke at the symposium. Afterward, she was asked if she would return to Milwaukee to help tell the city’s water story.

As Miss recalls, a group of civic leaders were part of WaterMark’s original Advisory Committee, which included Kevin Shafer, the head of the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewer District. With this group’s help, Miss spent a year familiarizing herself with the water issues across Milwaukee, as well as meeting and speaking with locals.

“The fabric of the city with its vertical markers — its many steeples and stacks along the rivers — suggested the imagery for the project,” she says. “The concept emerged of an ‘atlas of water’, where the stories of water are called out around the city.”

To that end, Miss says the stack at the Jones Island Water Treatment plant emerged as the focal point of the project. With the plant as a beacon, call-and-responses messages about storm water overflows could be sent out and received. As the project’s collaborators envisioned it, messages would echo through the WaterMarkers installed across the city.

“I was interested in how the very visible waterfront stack of the water treatment plant could be repurposed as a beacon to communicate messaging about water issues for the city,” Miss explains. “Very early on, I became interested in how this could be a project at the scale of the city and how artists could be integral to the process of revealing the many diverse narratives of the city.”

MMSD and the Advisory committee embraced this direction and, over a five-year period, the group began the process of artist and community engagement. Polly Morris, the Director of Lynden Sculpture Park, introduced Miss to a number of Milwaukee artists. To date, CALL has worked with nearly a dozen local artists on the first four active WaterMarks sites. Artists Melanie Ariens, Jill Sebastian, and Colin Matthes have been working on the UCC Acosta site, while Gabriela Riveros, Mollie Oblinger, and Jessica Meuninck Ganger are working on the Pulaski Park location at the Kinnickinnic River. Elsewhere, Portia Cobb and Fatima Laster are working on the 30th Street Corridor location, and Erick Ledesma, Sarah Gail Luther, and Jim Wasley are on the Greenfield site.

Aaron Asis, Urban Designer & Project Designer at CALL, says the first WaterMarker was installed at the UCC Acosta Middle School site in 2018. It featured stories and works from students who attend the school. Four to six additional WaterMarkers are scheduled to be fabricated and installed throughout 2020 and 2021 at Pulaski Park, Kinnickinnic River, 30th Street Corridor, and three along the Greenfield Avenue locations. Each WaterMarker will contain WiFi-accessible digital content featuring the voices of local residents and artists, programmed to flash information prior to a heavy rainstorm. These flashes will help notify residents to reduce water consumption until the storm passes, alleviating pressure on the water treatment infrastructure.

WaterMarker installation at Acosta Middle School // Image by Poblocki Signage Company

Community Action

Travis Hope, a Milwaukee community organizer, emphasizes that water has always been a part of the fabric of Milwaukee, long before its modern incarnation. Water, both in Lake Michigan and in the various rivers that empty into it, are what made the city what it is today. Before European settlement, Native American tribes used the waterways as a source of food, trade, and transports. After the Industrial Revolution, Lake Michigan and Milwaukee’s waterways evolved into engines of modern commerce.

Since 2014, Hope has been a volunteer with and later president of the Kinnickinnic River Neighbors in Action. A local community organization, KRNIA organizes events throughout the neighborhood, including Kinnickinnic River cleanup projects. The smallest of Milwaukee’s three rivers (the others being the Menominee and the Milwaukee), the Kinnickinnic is also the most densely populated. The KK, as it is referred to by residents, now flows into an area occupied by the Jones Island Water Treatment Plant..

“I think my interest is more in people and community, but to have a healthy one you need good water for both physical and mental health,” says Hope. “And this project really touches on the importance of water and how it affects all aspects of life.”

Along with the Sixteenth Street Clinic, a public health clinic in Milwaukee, Hope organized neighbors and educated them about the WaterMark project. Meetings and walks were held, with residents ultimately voting on artwork along the KK and the letter “Ñ” on the WaterMarker.

“Neighbors were also able to share stories about the river and things they hope to see in the future,” says Hope. “To be installed and become a gathering place, as well as a useful tool in conserving water during rain storms and bringing awareness to why we should conserve water and take care of our waterways for the future.”

“This is a great project for the neighborhood and I can’t wait to see it up and working,” he adds. “I as well as the KK River Neighbors in Action, Sixteenth Street Clinic, MMSD, Alderman José Perez, neighbors, and others will continue to inform the neighborhood on the WaterMarks project.’

Local residents participate in a CALL/WALK as part of WaterMarks community engagement program.

Designing WaterMarkers

Since WaterMark’s inception in 2014, CALL has looked at a wide variety of solar options and what Asis calls “design fantasies”. Most designs proved to be exactly that — fantasies.

“This past winter we were dealing with some very specific electrical challenges and chose to revisit our solar options,” says Asis. “We researched solar technologies around the globe to consider our options, but SolarTonic’s technical track record, comfort with prototyping, and location in the Midwest (Michigan) really helped make our decision seem like a no-brainer.”

SolarTonic has been involved in a number of community-related projects over the years. To design and build the WaterMarkers, SolarTonic collaborated with two other companies. Ignition Arts, an arts fabrication company out of Indianapolis, is handling the WaterMarkers’ digital components. Meanwhile, the signage is being designed by Poblocki Signage, a local Milwaukee sign fabrication company that is fabricating the letters and handling the installation.

Harry Giles, founder of SolarTonic, says the WaterMarkers project is built on its solahub technology. He describes solahub as a “total Internet of Things (IoT) platform”, configured for smart devices, mounted on a solar-powered framework, and remotely connected through wireless communications. Giles says it can be configured to manage a variety of tasks, including “safety, services, mobility, planning, sustainability, maintenance, transportation, and communications”. It does so through remote cloud-based monitoring and control of “security, messaging, illumination, mobile networks, environmental sensing, pedestrian movement, parking, and traffic flows.”

“Typical framework installations are integrated into poles, roadway portals, signage structures, bus shelters and canopies,” says Giles. “Solahub can be located anywhere it is needed, independent of electrical supply and cable connections.”

The team at Solar Tonic work on the solar powered poles at the core of the WaterMarkers

The WaterMarkers will be mounted on a solar-powered pole that will be connected to wireless communication networks.

“For the WaterMarks project, we are uniquely integrating solar power and wireless network communications into their solahub framework pole system, that supports a smart sign which is illuminated at night and signals flooding events,” says Giles. “When flooding is forecast, the sign lighting will pulse a warning to the local community, as a visual signal to take action to cut water consumption in order to reduce flooding of the city stormwater system.”

The WaterMarks warning signal will be activated by monitoring the Milwaukee city website, which advises on flooding incidents. Additionally, solartonic’s solahub platform will give WaterMark’s a local Wi-Fi access point for community members to connect to on their mobile devices, allowing them to gather more information about and interact with the WaterMarks project. Solahub’s flexibility and autonomy will allow WaterMarkers to be placed anywhere, with no need for electricity, fiber optic cables, or other wired network communications to be connected to the internet.

“This autonomy makes the SolarTonic platform ideal for placement all across Milwaukee for the WaterMarks products,” says Giles. “We’re very excited to be involved in WaterMarks. We love to interface with community-based projects — we think it’s very important. Our philosophy for how we operate is very sympathetic and conducive to these applications.”

Giles believes a lot of cities will see this type of project in the near future. Projects that are both art-based and community-focused, giving residents significant meaning in terms of real-life experience that they can touch, feel, and see within their environment.

The plan for WaterMarkers throughout Milwaukee’s inner harbor.

Milwaukee’s WaterMarks & Beyond

“In Milwaukee we are modeling how to engage residents with issues of the environment, equity, and health with the creation of a network of individual sites that are activated over time by a coalition of city agencies, academic institutions and community organizations,” says Miss. “The goal would be for other cities to be able to adopt a similar approach.”

Ultimately, CALL’s Miss hopes the WaterMarks project will help people realize that arts and culture have essential roles in addressing the most complex issues of our times. She sees this work as being complementary to that of scientists, educators, policy makers, and planners.

“Can we give artists the needed support to take the lead on creating an uplifting, empowering narrative for the public realm?” Miss muses. “This will be one that recognizes interconnections between nature and culture, between knowledge and experience, between opposing political views, communities with diverse perspectives, between art and science.”

Mary Miss at Milwaukee’s inner harbor

Ideally, WaterMarks and other CALL projects can help spread the world — help people picture what might come next. To deal with the complex and pressing issues of our times, Miss believes two things have become increasingly clear: people must figure out how to do projects at the scale of the city, not just single sites; and engagement must be sustained over time.

“We must forge these connections with imagination, dialogue, collaboration, and respect while embracing the complexity of the endeavor,” says Miss. “But most of all, this message must be a moving one, able to connect with people’s own experiences in their own communities. A heartfelt narrative that demonstrates how we can link our everyday lives to a Future of Resilience.”