Mary Miss, an introduction

Mary Miss has had a 50 year career expanding the role of art. Her work has deepened over her career with increasingly involved collaborations with other artists, architects, landscape architects and finally, with the founding of City as Living Laboratory, with experts in all fields. What has remained consistent is her desire to investigate the built environment and how the public engages with the built systems they often take for granted.

After receiving an MFA from the Rinehart School of Sculpture, Maryland Institute College of Art in 1968, Mary Miss moved to New York where she exhibited with artists like Alice Aycock and Jackie Ferrara, who collectively became known as early feminist sculptors. Miss later became a founding member of the Heresies Collective, a group of feminist political artists, who’s primary output was a magazine of the same name, which ran from 1977 to 1993. Miss’s early works are glimpses of structures that have an air of familiarity that might be easily overlooked. In Miss’s hands, however, these structures provoke a greater curiosity about how and why we build, about how we take the world around us for granted. They are paradoxes, existing in an uncanny space between minimalist and concept – almost ready-made but not, almost pure form, but still colloquial.

Art historian Jörg Heiser posited “that the crucial point of minimal art is to establish a spatial relation between viewer and object, heightening the viewer’s self-awareness.” Institute of Contemporary Art, London, curator Karen Linker articulated a similar idea in relation to Miss’s minimalist early work, “Cones, grates or awning-like forms were worked with tar, wire mesh, canvas or wood; the resulting objects, possessing their own unmistakable physical attributes, emitted associations at once potent yet elusive of definition. The materials were chosen for their appearance and availability, and the directness of their construction, so alien to 1960s industrial finish. But they were also chosen for their general cultural accessibility, indicating a focus on the viewer, unusual for the period.”

The work I have done has always had a realistic, physical motive, rather than an abstract and conceptual basis. It uses particular instances of situations or material objects; the pieces are not dreamt up apart or away from the circumstances.

- Mary Miss, ArtForum, 1973

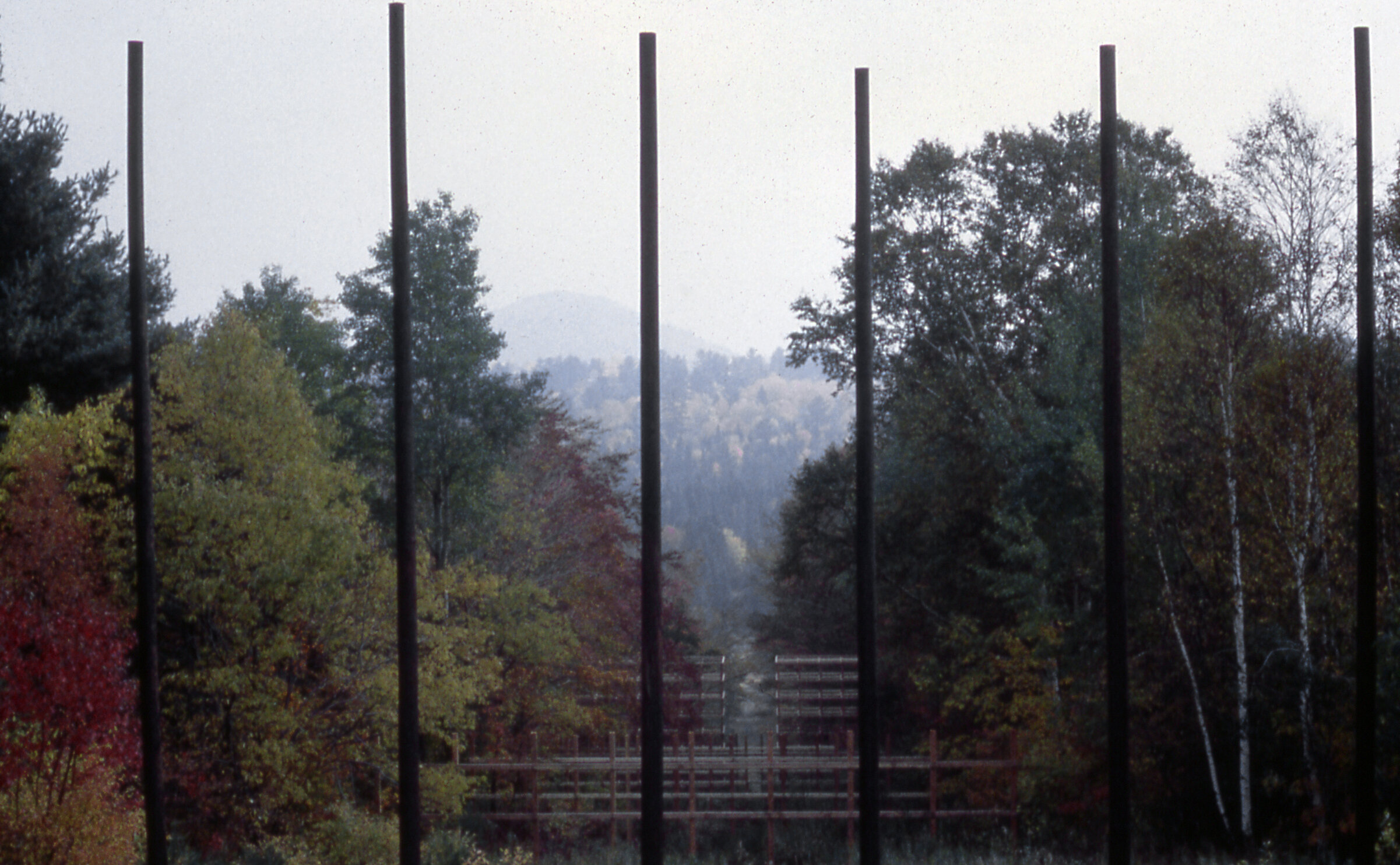

Miss began experimenting with what later became known as Land Art. “This piece happens when you get there & stand in front of it,” art critic and curator Lucy Lippard, another core member of the Heresies Collective, wrote about the 1973 Battery Park Landfill project, “as the modestly sized holes are perceived, they expand into an immense interior space...the plank fences become what they are — not the sculpture but the vehicle for the experience of the sculpture, which in fact exists in this air, or rather in distance crystalized.”

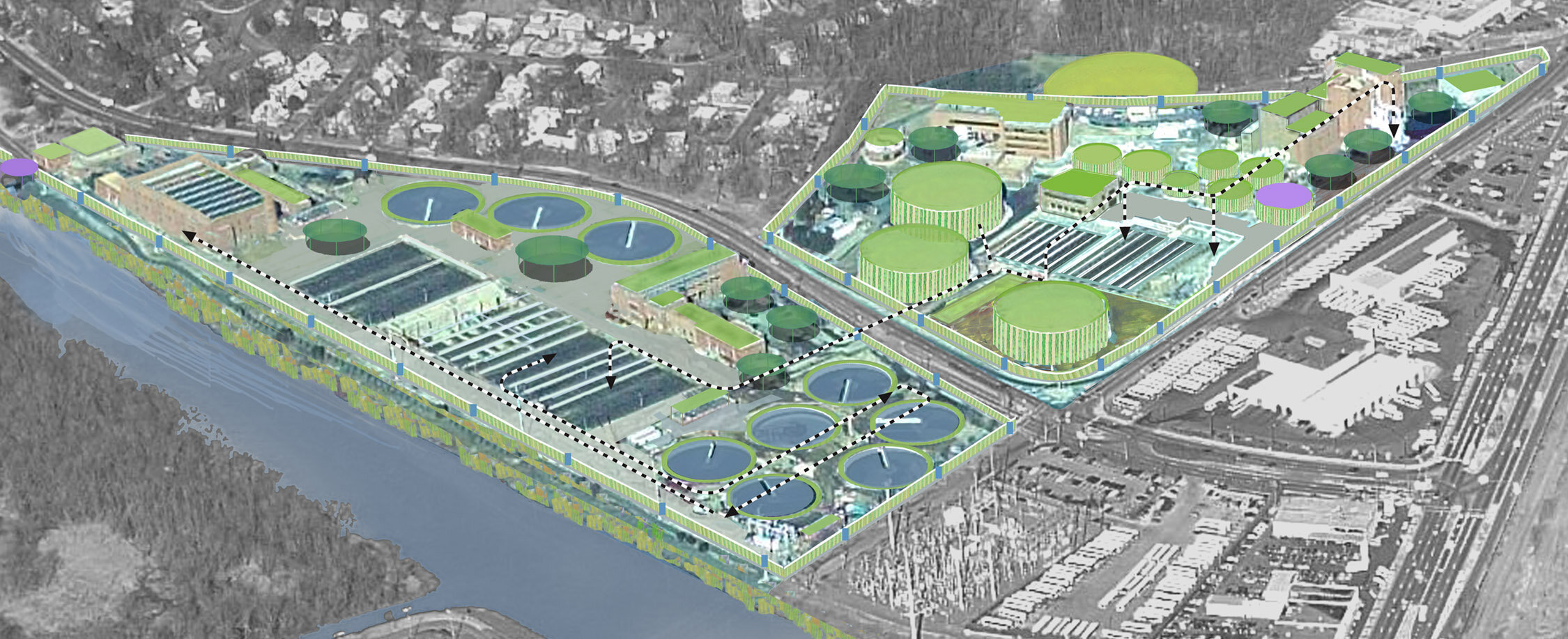

Then, Miss did something different: She made a sculpture in the earth that one looked at from above. As if to defy expectations, she began building towers and decoys of playful proportions, and the single objects that we were once asked to consider became large structures that required us to rediscover how to inhabit them. Art critic Rosalind Krauss describes this shift in Miss’s work to articulate a new consideration of sculpture's interdisciplinary nature, between architecture and landscape, in her seminal 1979 essay Sculpture in the Expanded Field. That same year, Miss participated in Robert Morris’s design symposium Earthworks: Land Reclamation as Sculpture, sponsored by the Kings County Arts Commission, which proposed creating large scale sculptures that use the earth as a medium to rehabilitate technologically abused land. By involving contemporary artists in land reclamation, the King County Arts Commission took an approach that no governmental agency had yet attempted on any significant scale.

In her landmark 1986 essay, “A Redefinition of Public Art,” Miss wrote, “art must be experienced directly.” Discovering what direct experience is has been the focus of much of Miss’s work, an expedition from representations of spaces that appear familiar but are beguiling, to landscapes where a narrative is unearthed, and finally to spaces in which the viewer participates in determining what the experience and meaning might be.

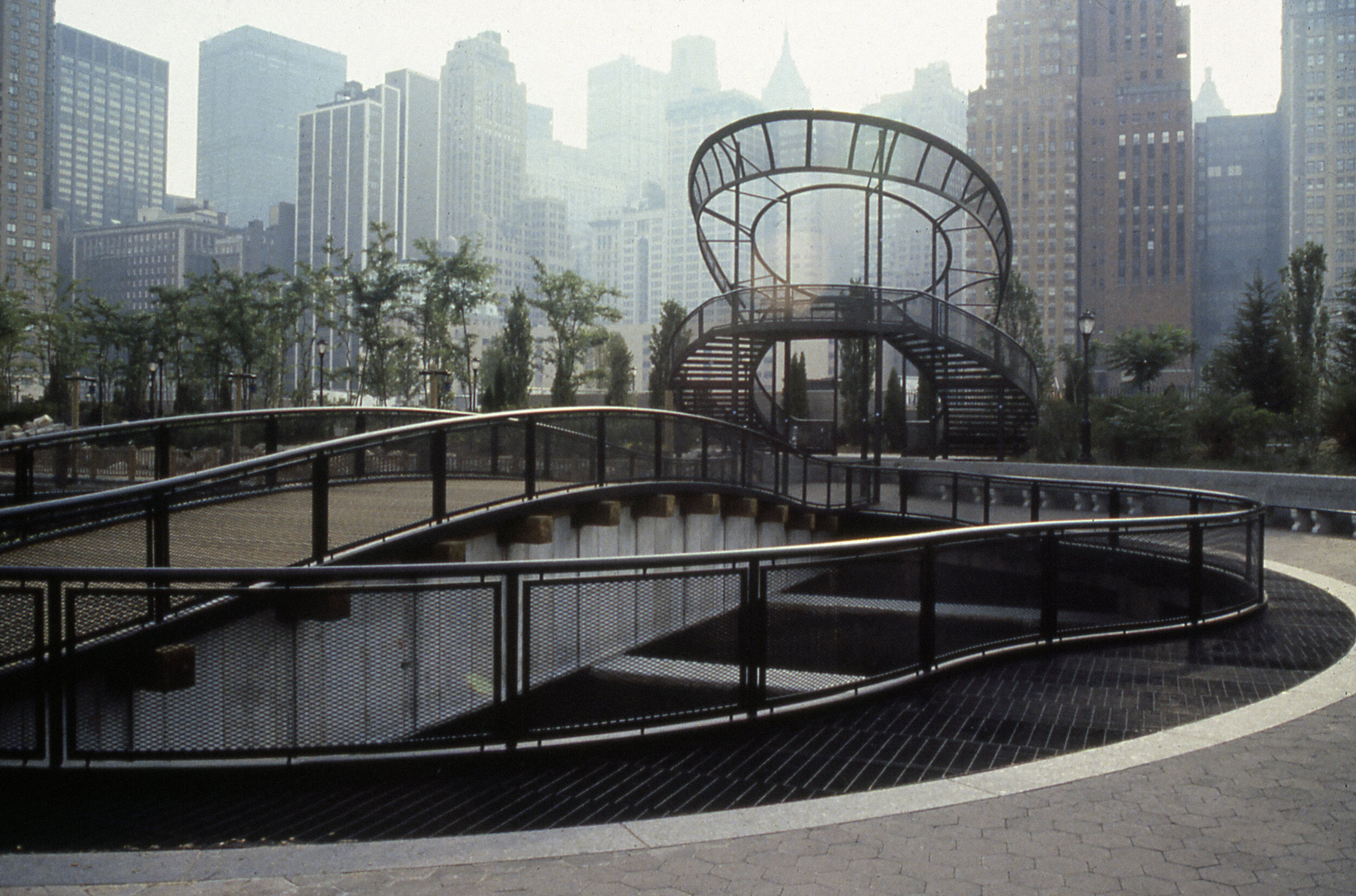

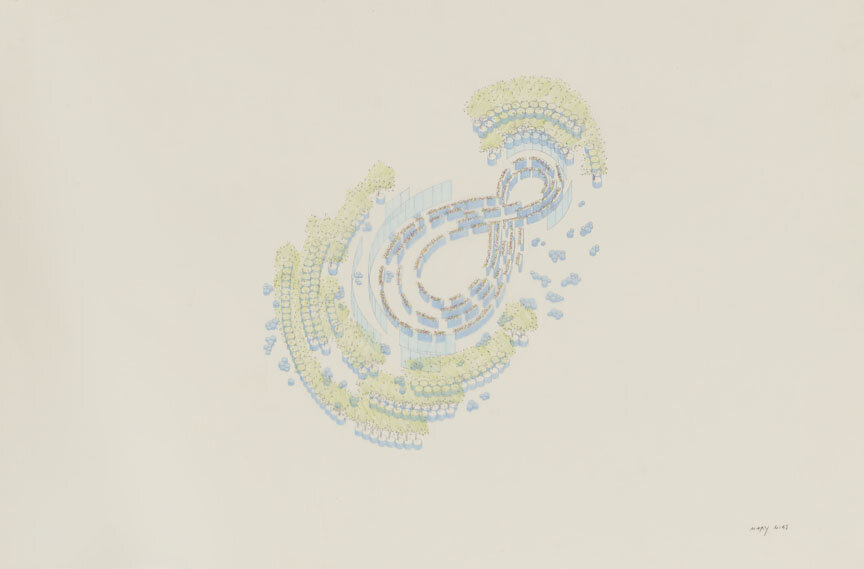

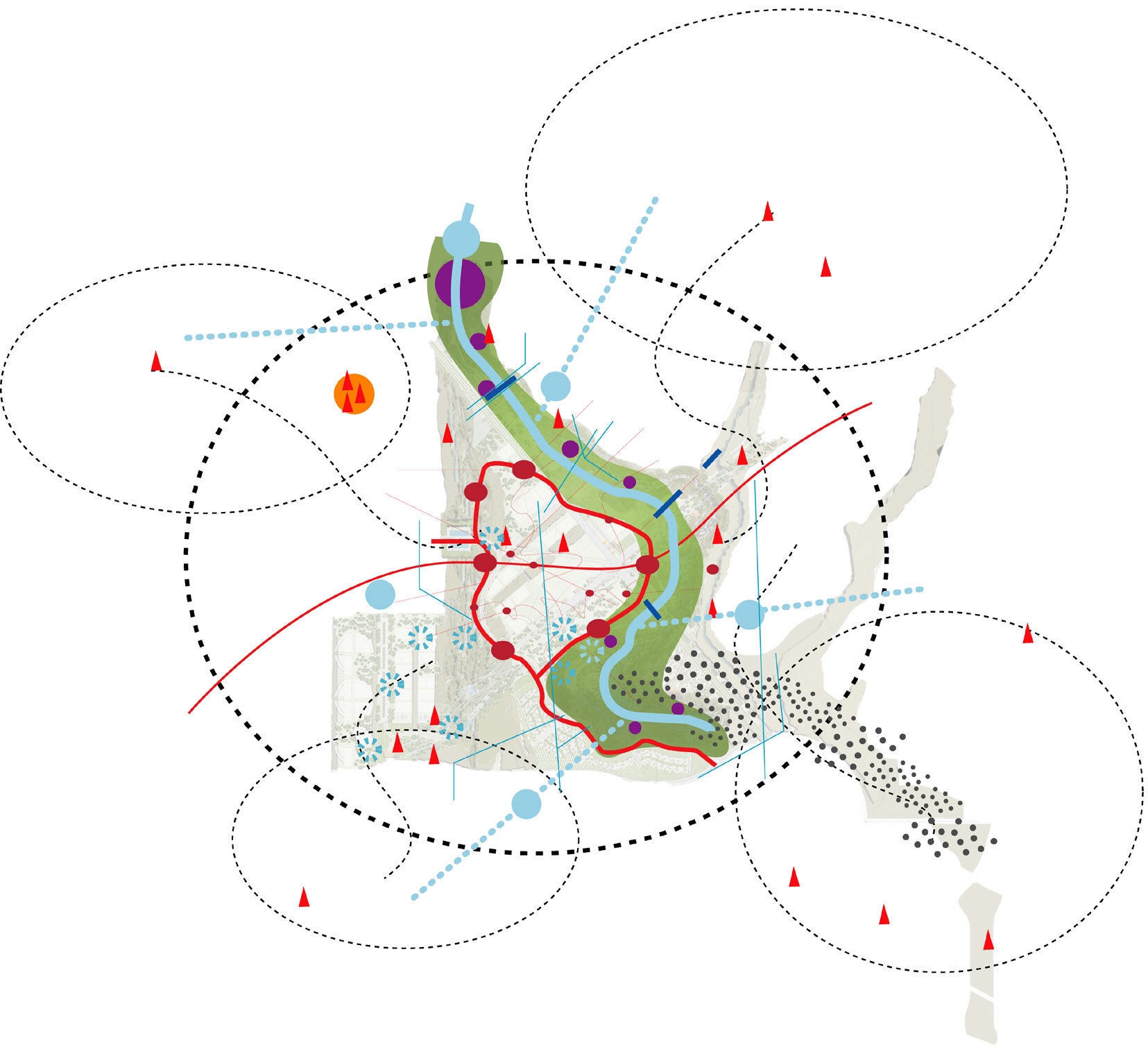

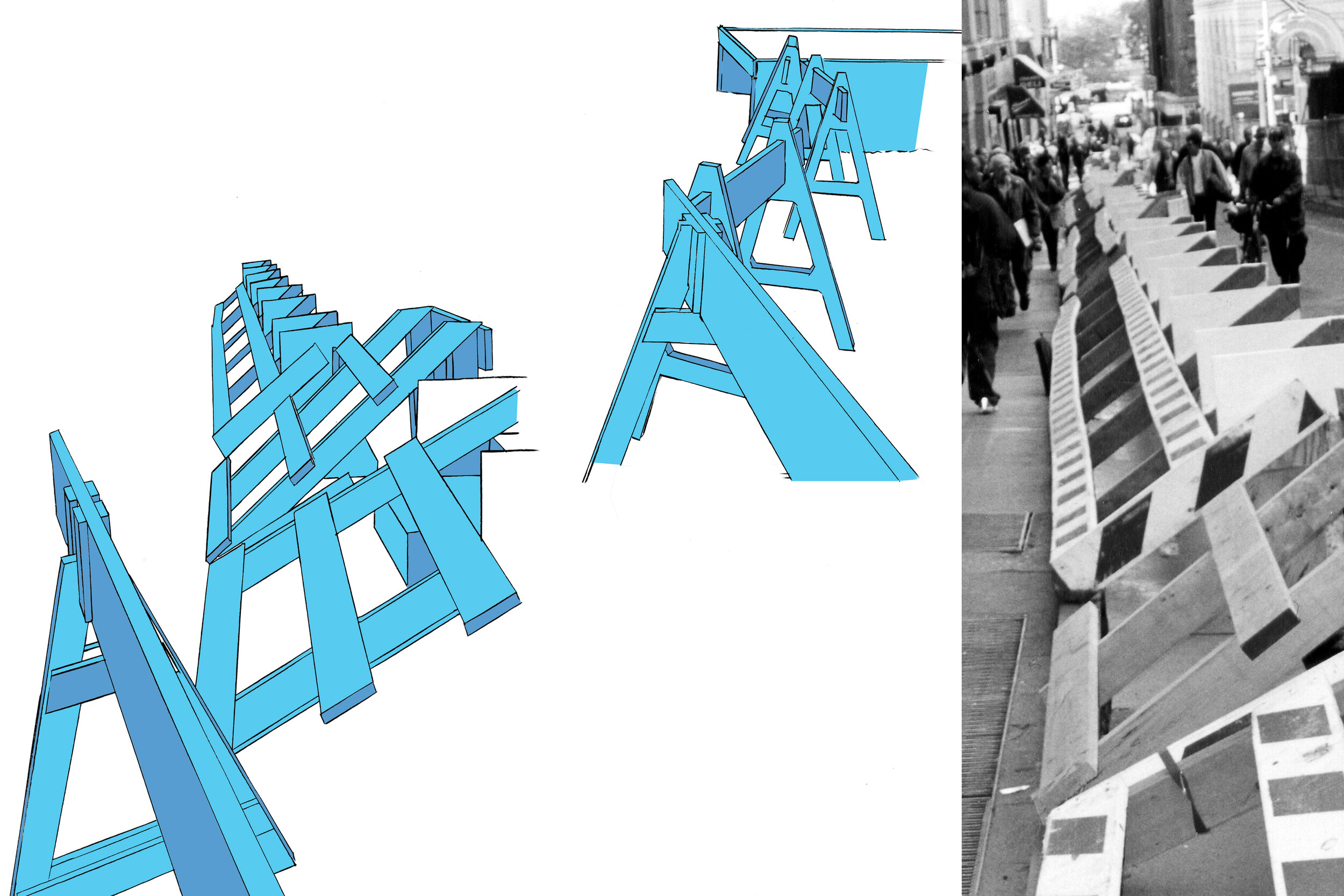

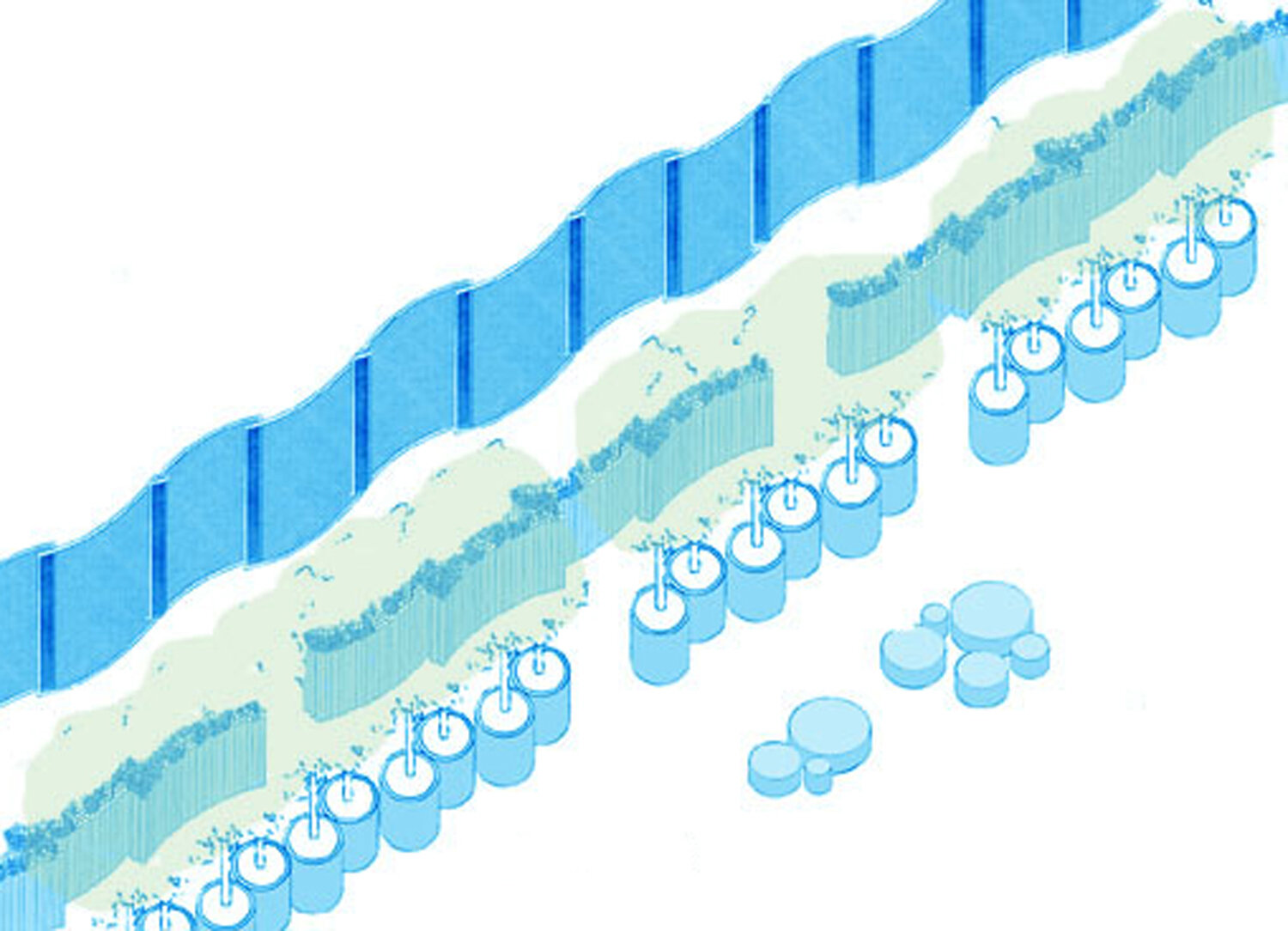

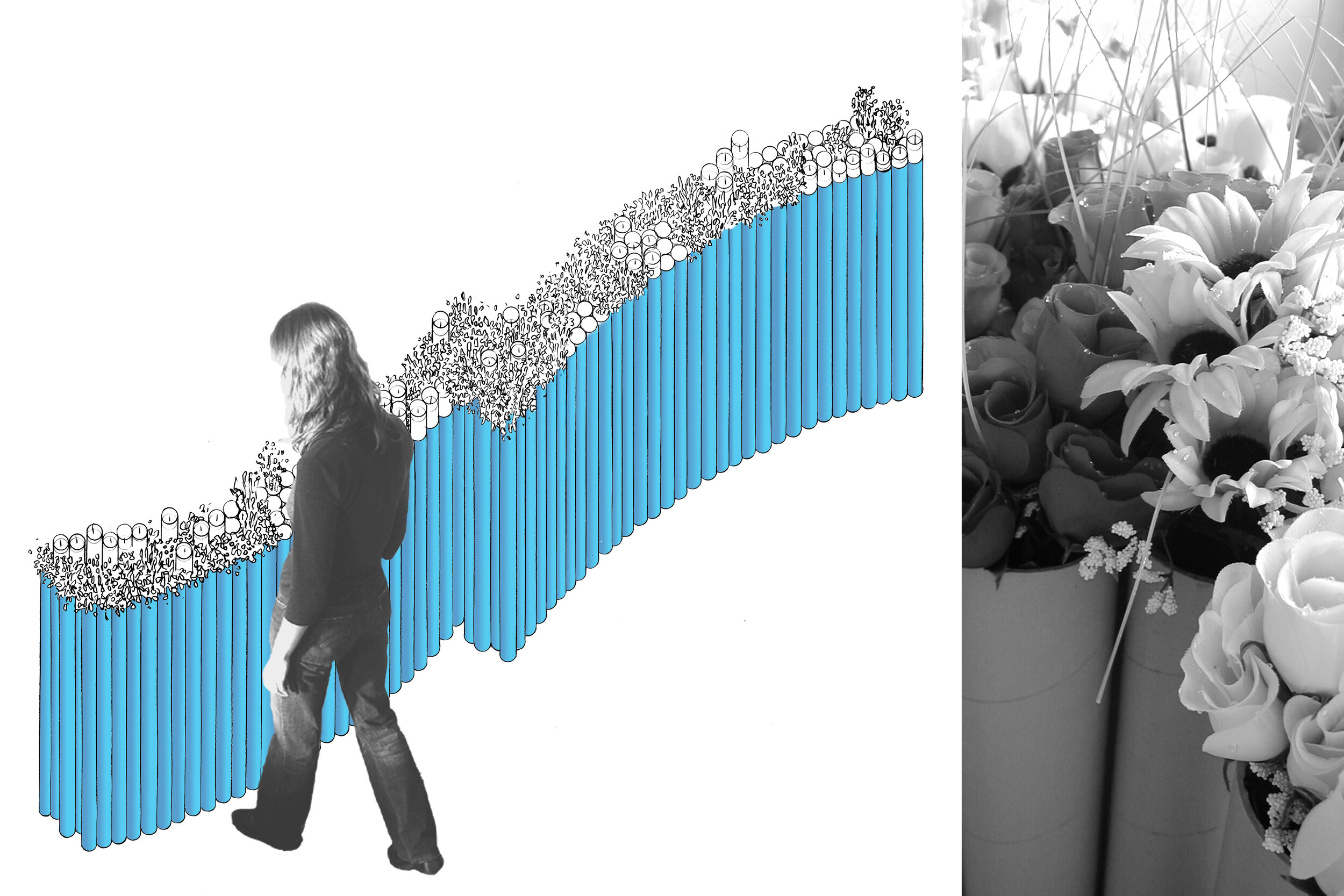

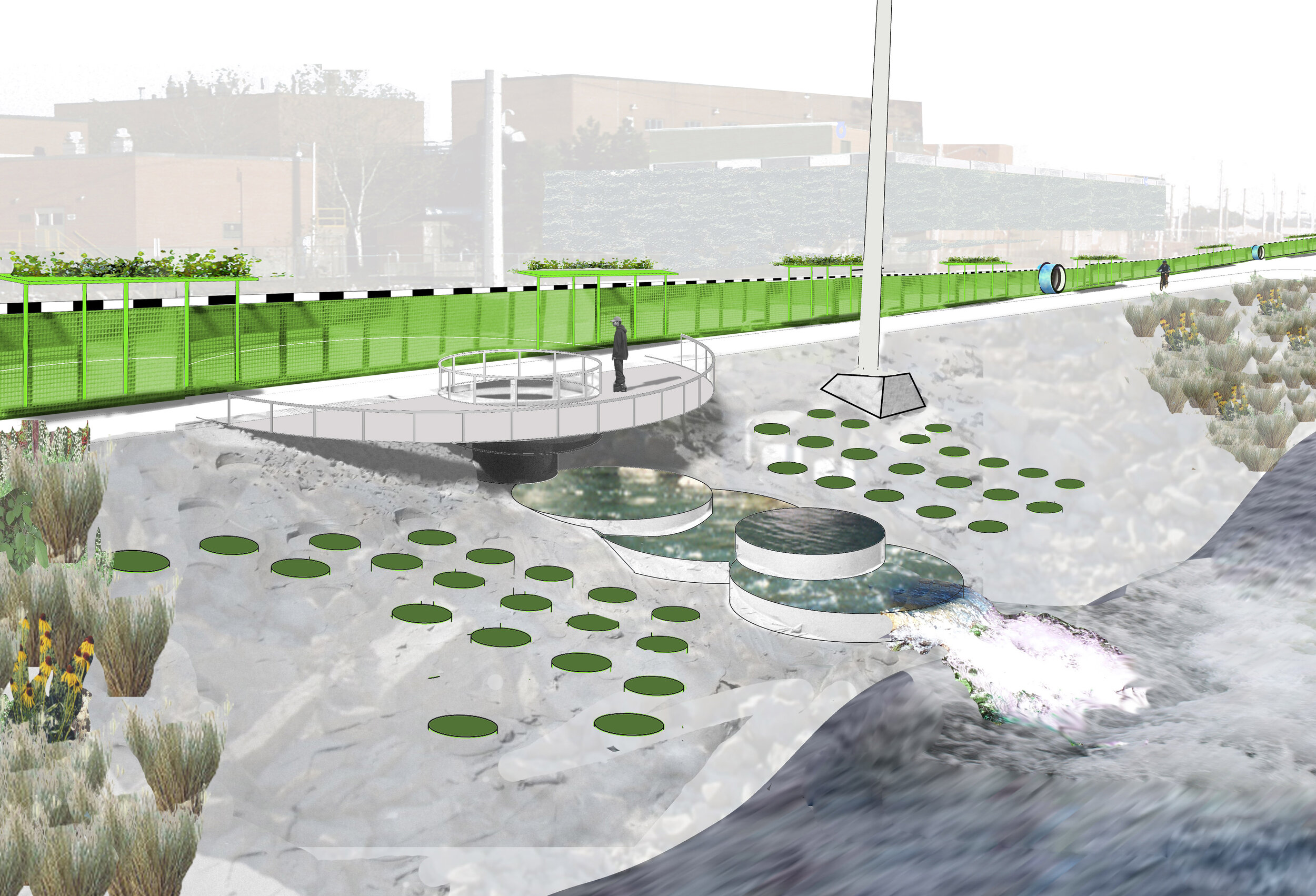

Reading Lippard on Miss’s 1973 temporary installation, Battery Park Landfill, is remarkable, and her insights are ever pertinent. When Miss returned to Battery Park City to build the South Cove viewing platform — a landmark of collaboration between artists and the public — the intention was to make the water more accessible to people living in lower Manhattan. Even as Miss’s work developed, as her sculptures dug down, built up, and rearranged space, her work always needed participation, a component of experience. As such, it feels natural for Miss, as her work has expanded beyond New York studios and galleries, beyond the lawns of college campuses, into huge expenses – subway stations, abandoned rail yards, the White River Watershed, the Broadway Corridor – that participation in the work would need to be bigger and more direct as well.

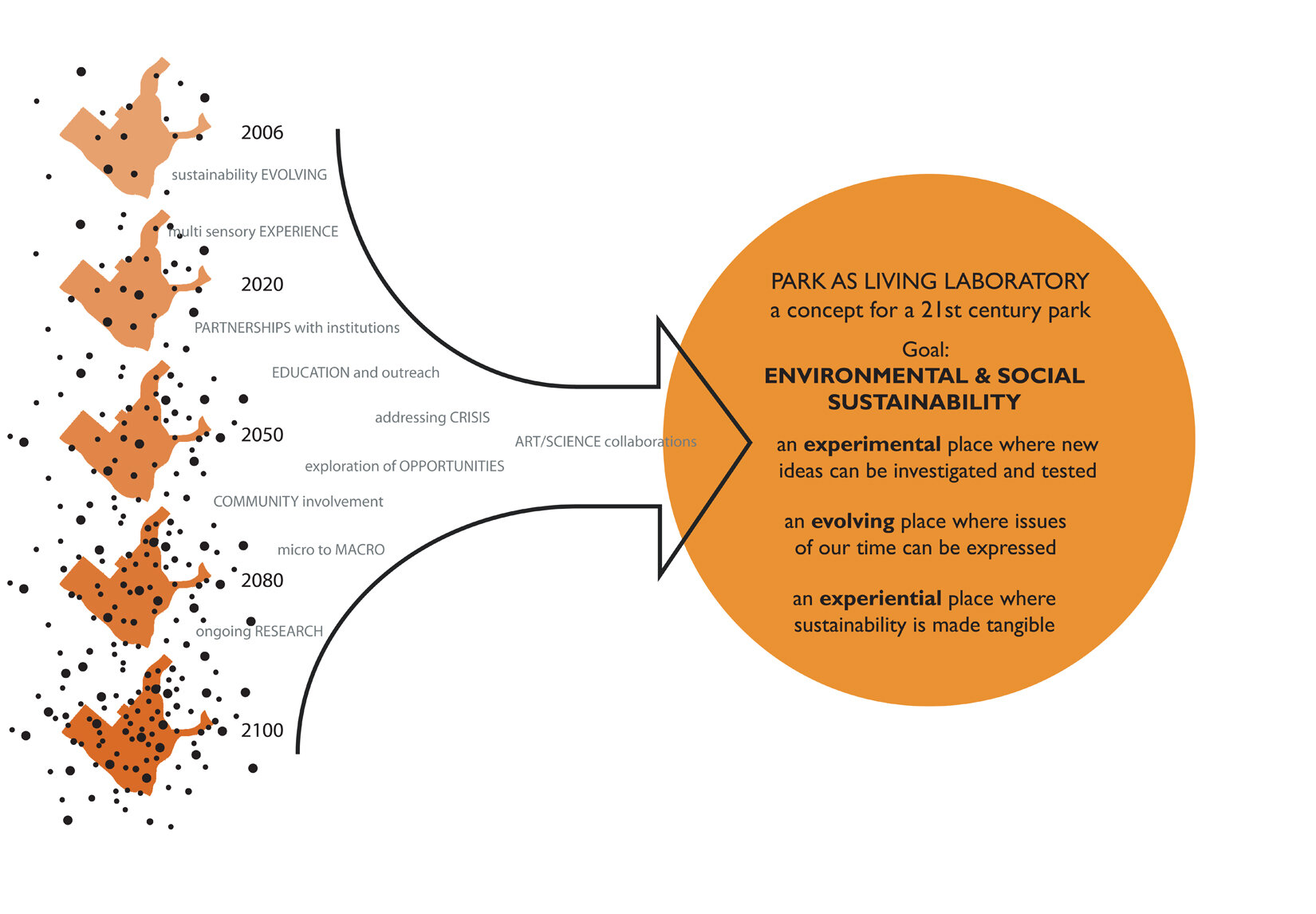

Mary Miss conceived of City as Living Laboratory as a forum to make rich opportunities for public participation in art and design, in our infrastructure and our ecology. In her upcoming book, she identifies six projects from 2001 to when she founded CALL in 2008, as the groundwork for City as Living Lab: Moving Perimeter; Santa Fe Railyard Park; Arlington County Water Pollution Plant; Orange County Great Park: Park as Living Laboratory; Connect the Dots; Roshanara’s Net.